White Paper: Audit Risk for Captive Insurance Companies

Use of Small Captive Insurance Companies as Abusive Tax Shelters

Executive Summary

The issue:

Significant abuse of small captive insurance companies (CICs) as tax shelters has earned CICs a place on the IRS’s 2015 “Dirty Dozen” list of tax scams. Tax advisors, companies with CICs, and companies looking to establish CICs should be aware of the increased tax audit risk related to CICs.

Challenge:

How do you avoid the IRS’s perception of an abusive tax shelter? This requires establishing a reasonable economic basis and properly pricing insurance premiums.

Insurance policies were developed to hedge against contingent and uncertain economic losses. Typical insurance vehicles pool risk across numerous individuals or companies. CICs, by design, are limited to an individual company; therefore, the insured risk must be suitable for a CIC. Additionally, the pricing of insurance premiums should be equivalent to third-party, arms-length pricing.

Solution:

ValueScope’s team of experts have the knowledge and experience to determine if existing CICs have the economic substance necessary to survive audit scrutiny. Additionally, we have the skills and expertise necessary to assist CICs to properly structure their policies in order to avoid potential issues.

Captive Insurance Companies

A Captive Insurance Company (CIC) is an insurance company established by an operating parent company for the purpose of covering the parent company’s specific risks. CICs are effectively a type of “self-insurance.”

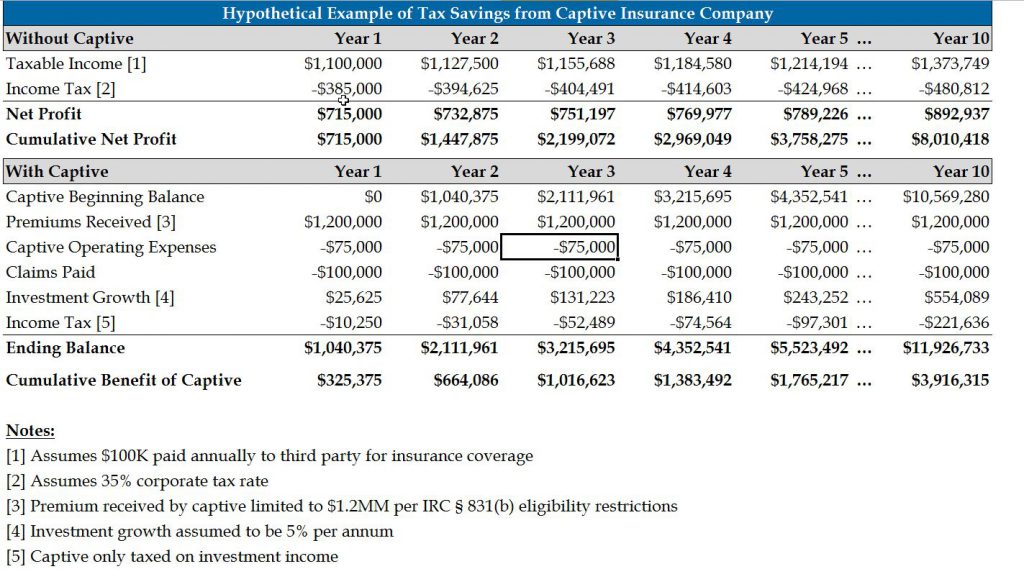

In this hypothetical example, without the CIC, the operating company has $1.1MM in taxable income in year 1 net of its $100,000 in insurance premiums. After paying taxes at 35%, the company’s net profit is $715,000. With the CIC, the company pays the $1.2MM (i.e., the $1.1M in taxable income plus the $100,000 that would have been paid to a third party insurance company) to its CIC. The CIC has operating expenses of $75,000 annually that it pays to the captive manager and also pays any insurance claims filed by the parent. In the example above, we assume the claims paid by the CIC to the parent are $100,000 annually. The assets in the portfolio are invested and generate an investment return, assumed to be 5%. The only taxes associated with the CIC are on the investment income. The economic benefit of the CIC in this example is $325,000 in year 1 and over $3.9 MM over ten years. This economic benefit is created purely by forming a CIC and sheltering income for taxation.

Challenge: Avoiding Abusive Small CICs

Given recent IRS scrutiny, creating small CICs deemed abusive, like the hypothetical example above, should be avoided. These CICs are formed primarily for the purpose of sheltering income from taxation and lack economic substantiation for the premiums charged to the parent. To shelter income from taxes, abusive CICs set insurance premiums that are well in excess of what would reasonably be expected in any third-party transactions. For example, a recent New York Times article gives an example of a dental practice self-insuring against a terrorist attack, a risk that while (remotely) possible has such an extremely low probability of occurrence that it is unlikely to have any significant impact on the value of the dental practice or to be separately insured against in the real world.

It is important to realize that insurance is typically sold and designed to “share” risk across a large number of insured parties that face similarly ratable risks (a “risk pool”). The traditional economic purpose of insurance is to diversify the risk of adverse events across a large number of insured parties that are individually risk averse. Each insured party is willing to pay a premium to the insurer in order to cover infrequent but extreme risks for the insured. An insurance company sets premiums based on the expected losses in the insured pool (based on the “loss ratio”), the expenses incurred by the insurer, and the profit required by the insurer. In exchange, the insurer provides the capital and organizes and pools the risks sufficiently to reliably protect each insured. The insurer may often join with other insurers to form larger risk pools or obtain insurance against the most extreme events through reinsurance with other carriers. Considering these economics, a CIC is not suitable for certain types of risks faced by businesses because it is not able to pool risks across a large set of insured parties (having only a single insured party) and does not have the size and financial resources required to protect the insured parent against certain types of extreme adverse events.

The challenge, then, is to establish the reasonable economic basis for insurance through a CIC and then properly price such insurance in order to avoid an unfavorable tax audit outcome. Given current IRS scrutiny of this issue, we recommend that a business with a CIC properly documents and measures the adverse risks faced by the business that are insured by the CIC, and then to price the insurance coverage appropriately based on such risks. Absent adequate documentation and support, setting up a CIC could expose a business to significant audit risk.

So, what risks warrant the use of a CIC? Risks that are material to the value of the business and are potentially insurable (i.e., irregular in timing and amounts) are typically the best risks to insure through a CIC. A CIC can be effective at offsetting such risks for the insured parent over time, especially after it has built up a sufficient reserve of captive assets. The CIC may also acquire reinsurance (or a high-deductible policy) to protect against the more extreme risks that a CIC may not be well suited to insure against.

Most Suitable Industry Types for CICs

In this hypothetical example, without the CIC, the operating company has $1.1MM in taxable income in year 1 net of its $100,000 in insurance premiums. After paying taxes at 35%, the company’s net profit is $715,000. With the CIC, the company pays the $1.2MM (i.e., the $1.1M in taxable income plus the $100,000 that would have been paid to a third party insurance company) to its CIC. The CIC has operating expenses of $75,000 annually that it pays to the captive manager and also pays any insurance claims filed by the parent. In the example above, we assume the claims paid by the CIC to the parent are $100,000 annually. The assets in the portfolio are invested and generate an investment return, assumed to be 5%. The only taxes associated with the CIC are on the investment income. The economic benefit of the CIC in this example is $325,000 in year 1 and over $3.9 MM over ten years. This economic benefit is created purely by forming a CIC and sheltering income for taxation.

Challenge: Avoiding Abusive Small CICs

Given recent IRS scrutiny, creating small CICs deemed abusive, like the hypothetical example above, should be avoided. These CICs are formed primarily for the purpose of sheltering income from taxation and lack economic substantiation for the premiums charged to the parent. To shelter income from taxes, abusive CICs set insurance premiums that are well in excess of what would reasonably be expected in any third-party transactions. For example, a recent New York Times article gives an example of a dental practice self-insuring against a terrorist attack, a risk that while (remotely) possible has such an extremely low probability of occurrence that it is unlikely to have any significant impact on the value of the dental practice or to be separately insured against in the real world.

It is important to realize that insurance is typically sold and designed to “share” risk across a large number of insured parties that face similarly ratable risks (a “risk pool”). The traditional economic purpose of insurance is to diversify the risk of adverse events across a large number of insured parties that are individually risk averse. Each insured party is willing to pay a premium to the insurer in order to cover infrequent but extreme risks for the insured. An insurance company sets premiums based on the expected losses in the insured pool (based on the “loss ratio”), the expenses incurred by the insurer, and the profit required by the insurer. In exchange, the insurer provides the capital and organizes and pools the risks sufficiently to reliably protect each insured. The insurer may often join with other insurers to form larger risk pools or obtain insurance against the most extreme events through reinsurance with other carriers. Considering these economics, a CIC is not suitable for certain types of risks faced by businesses because it is not able to pool risks across a large set of insured parties (having only a single insured party) and does not have the size and financial resources required to protect the insured parent against certain types of extreme adverse events.

The challenge, then, is to establish the reasonable economic basis for insurance through a CIC and then properly price such insurance in order to avoid an unfavorable tax audit outcome. Given current IRS scrutiny of this issue, we recommend that a business with a CIC properly documents and measures the adverse risks faced by the business that are insured by the CIC, and then to price the insurance coverage appropriately based on such risks. Absent adequate documentation and support, setting up a CIC could expose a business to significant audit risk.

So, what risks warrant the use of a CIC? Risks that are material to the value of the business and are potentially insurable (i.e., irregular in timing and amounts) are typically the best risks to insure through a CIC. A CIC can be effective at offsetting such risks for the insured parent over time, especially after it has built up a sufficient reserve of captive assets. The CIC may also acquire reinsurance (or a high-deductible policy) to protect against the more extreme risks that a CIC may not be well suited to insure against.

Most Suitable Industry Types for CICs

- Healthcare

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

- Construction

- Government Contractors

- Financial Services

- Single parent

- Series LLCs

- Risk Retention Group

- Rental

- Segregated/Protected Cell

- Association

- Agency

- Special Purpose Vehicles

- Businesses considering the implementation of a CIC should review the types of CICs listed above because the implications of each will vary depending upon intended use and industry type.

- Estimate hazard rates for common insurance risks,

- Estimate the amount of coverage that is reasonable and customary,

- Estimate insurance premiums that would reasonably be charged to the parent in a third-party, arms-length insurance transaction,

- Identify any unsubstantiated captive insurance premiums, and

- Document our findings in comprehensive and well-written reports that would survive IRS audit scrutiny.

Steven Hastings, MBA, CPA/ABV/CFF, CGMA, ASA, CVA

PRINCIPAL